Ten years since 2015 – what happened?

Ten years ago, 163,000 people sought protection in Sweden, of which 100,000 came during a few intense autumn months. This article focuses on the year 2015 – what happened and who came here.

Published 27 October 2025

In the years leading up to 2015, the number of asylum applications had increased, and in 2014, over 80,000 people had sought protection in Sweden. However, it was not known how sharp the increase would be in 2015.

During the first half of 2015, Sweden's share of the total number of asylum seekers in Europe had decreased. As late as July, the Swedish Migration Agency's forecast painted a picture of a Europe with an increasing number of asylum seekers, but where Sweden had lost its attractiveness due to long processing times and inadequate integration. This primary scenario would turn out to be wrong.

Asylum applications increased rapidly

From the end of July to August, the number of asylum seekers doubled, from around 1,500 to 3,000 people per week. During the autumn, the increase continued rapidly, and when the Swedish Migration Agency's next forecast was released in October, the number of applicants had reached over 9,000 per week.

In its October forecast, the Swedish Migration Agency described a situation unprecedented in modern times; a humanitarian crisis where the EU's fundamental principles and regulated asylum migration had been rendered inoperative. The authority's ordinary capacity and preparedness were insufficient; there was an acute shortage of accommodation, and extraordinary solutions were requested.

During October and November, Sweden received more than 20 percent of all asylum seekers in the EU+, three times more than during the first six months of the year.

When the number of asylum seekers in November reached around 10,000 per week, the Swedish Migration Agency's overriding goal became to provide shelter. This led to emergency placements, meaning dormitories, tents, hotels, and evacuation housing organized by municipalities across the country. Existing asylum accommodation was filled to capacity, and a number of other efforts were made to increase capacity.

Download the timeline for autumn 2015 (in Swedish) pdf, 18.2 MB, opens in new window.

Measures were taken to stop applicants

On 12 November, Sweden introduced border controls, specifically internal border controls against other EU countries. And on 24 November, the government held the historic press conference where temporary residence permits were introduced, asylum rules were tightened, and ID checks were announced on buses, trains, and boats to Sweden.

All of Sweden was affected

Authorities, municipalities, and large parts of the Swedish civil society were mobilised during the autumn of 2015. Private individuals and organisations met refugees at train stations, organised accommodation, collected clothes and necessities, provided legal and practical support, and many opened their homes to receive unaccompanied children.

By the end of the year, approximately 180,000 people were registered in the Migration Agency's reception system, including 100,000 in the authority's accommodation. This was more than a doubling from the previous year.

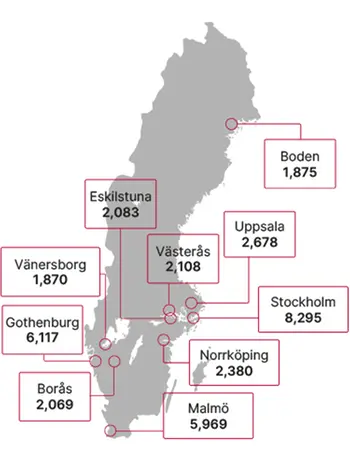

Municipalities across the country took on great responsibility for the reception. Some examples of smaller municipalities that had received many asylum seekers by December were Boden, Söderhamn, Lindesberg, Kramfors, Borgholm, and Hultsfred. Ljusnarsberg was the municipality in the country that received the most asylum seekers in relation to the number of inhabitants.

Zoom image

Zoom imageMap of Sweden showing which municipalities received the most asylum seekers in 2015.

Reception in the rest of the EU

During 2015, Sweden received around 163,000 asylum seekers, or 12 percent, of all those who sought protection in the EU. Only Germany received more (and Hungary*). In relation to the population, Sweden was the country that received the most of all EU countries, with the exception of transit countries such as Hungary where most applicants did not stay.

According to Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union, figures from March 2016, over 1.2 million asylum seekers came to the EU during 2015. In addition to the fact that Hungary's statistics can be questioned, some other figures have been revised retroactively. For example, Germany retroactively registered a very large number of asylum seekers only in 2016, and the Swedish Migration Agency's assessment is that they likely had closer to double as many applicants.

The figure for the Swedish reception also deviates from the Swedish Migration Agency's statistics (which was approximately 163,000 asylum seekers during 2015).

Read about the record year 2015 for first-time applicants External link.

Statistics on asylum reception 2015

EU countries that received the moast asylum seekers |

|---|

Germany: 441,800 |

(Hungary: 174,400) |

Sweden: 156,000 |

Austria: 85,500 |

Italy: 83,200 |

France: 70,000 |

Asylum reception per capita: Figures per 100,000 inhabitants |

|---|

Sweden: 1,600 |

Austria: 1,000 |

Finland: 590 |

Germany: 540 |

Luxembourg: 420 |

Denmark: 370 |

EU average: 250 |

Source: Eurostat.

Who were the arrivals?

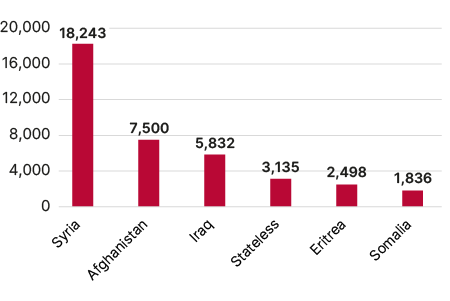

Approximately half of those seeking protection in the EU during 2015 came from Syria, Afghanistan, or Iraq. In addition to the war in Syria, a number of other factors contributed to lowering the threshold for people to seek refuge in Europe. Among other things, the Dublin Convention was inoperative, there were no barriers between Greece and the rest of Europe, while the costs of smuggling networks fell.

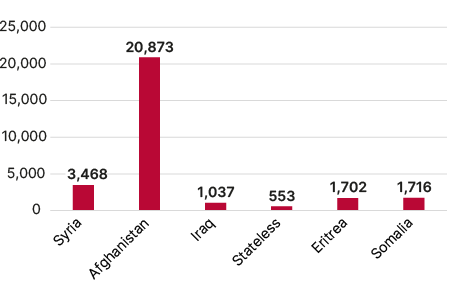

The war in Syria is reflected in the Swedish statistics on asylum seekers in 2015; it is the largest country of origin with 50,000 Syrians seeking protection here.

Syrian asylum seekers were in large part families; about half of all Syrians were children, and most came to Sweden with their families. Of Syrian asylum seekers, a relatively large number were also women, just over 18,000 compared to nearly 33,000 men.

Different ages and groups depending on citizenship

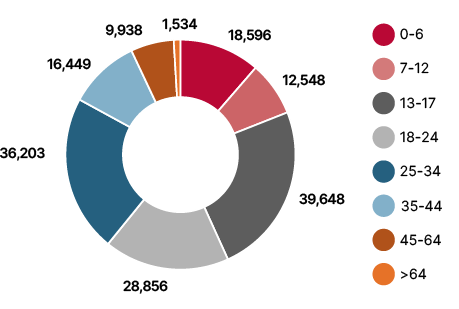

Afghans were the second largest group with around 42,000 asylum seekers, and approximately half of these, 21,000, were unaccompanied children. The vast majority of Afghan asylum seekers were men – nearly 37,000 compared to 7,500 women.

Iraq was the third largest country of origin with just over 21,000 asylum seekers in Sweden.

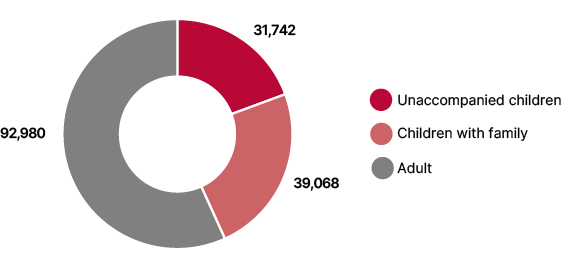

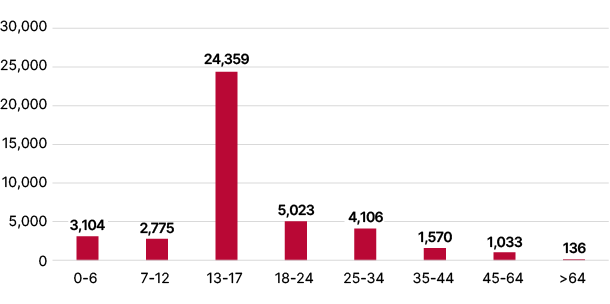

Of those who sought protection in Sweden 2015, over 90,000 were adults. Almost 40,000 were children who came with their parents and just over 30,000 sought protection as unaccompanied children.

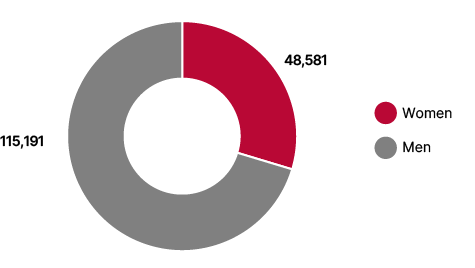

Among the children, the 13-17 age group was the largest. There were significantly more men than women who sought protection – nearly 50,000 women compared to just over 115,000 men.

Chart showing asylum seekers, broken down by gender.

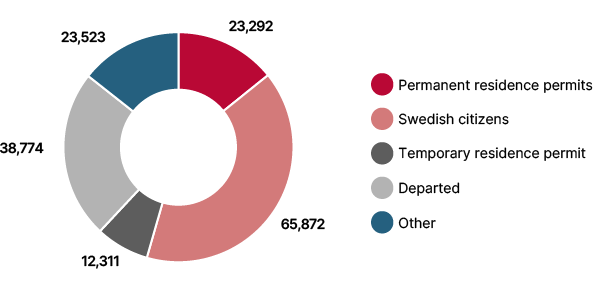

What has happened to those who arrived in 2015?

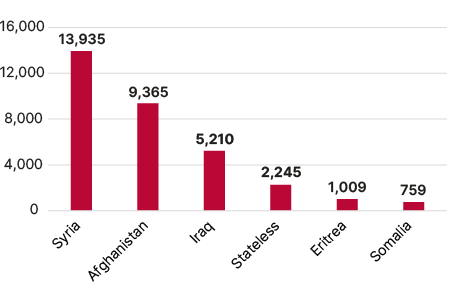

Of the approximately 163,000 who sought protection in Sweden during 2015, most remain in the country. Nearly 66,000 now have Swedish citizenship. Nearly 39,000 of those who sought protection that year have left the country and are registered as departed (there may be more who left Sweden without this being registered by the Migration Agency).

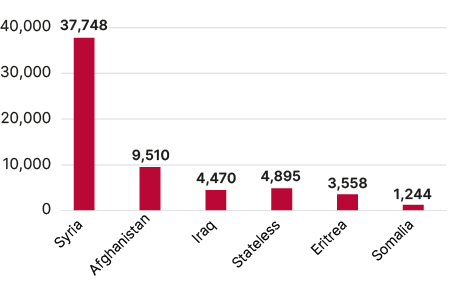

Syrians are the group where the most have applied for and received citizenship. In the group of Afghans, where a large proportion applied as unaccompanied children, the review has been affected by the temporary so-called "Upper Secondary School Acts" (gymnasielagarna). This, in addition to the lack of valid identification documents, is one reason why a relatively large number of Afghans currently have permanent residence permits (just over 11,000).

Read previous article about unaccompanied children

Among the Iraqis, a relatively large number have left Sweden after arriving in 2015 – nearly 10,000 of just over 21,000 applicants have been registered as departed.

Chart showing the current status of asylum seekers from 2015. The category ‘Other’ includes, among other things, deceased, departed or duplicate applications.

Chart showing the number of people who have been granted Swedish citizenship, broken down by citizenship of the person's country of origin.

Many families have been reunited

The Swedish Migration Agency's statistics on family reunification include, in addition to the families of those seeking protection, other groups, such as relatives of Swedish citizens who wish to obtain a residence permit. Therefore, it is not possible to precisely distinguish how many relatives during/after 2015 wished to settle here with a person who received protection in connection with that.

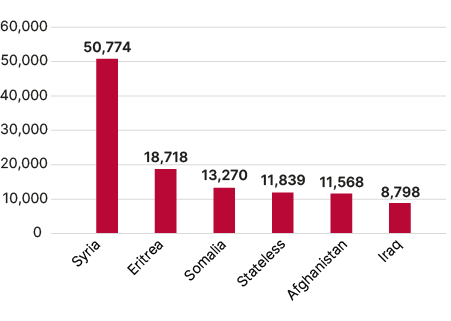

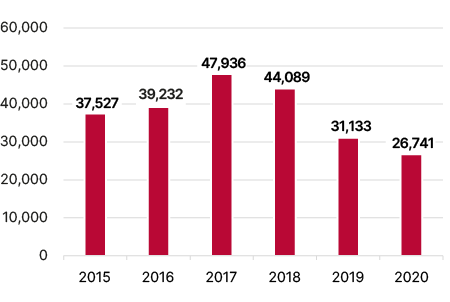

However, one can look at the country of origin over the five-year period 2015-2020 to get an approximate picture of how the 2015 asylum reception affected the family reunification statistics.

At that time, the six largest nationalities were conflict-affected countries from which many had sought asylum in Sweden. Syria is clearly the largest country of origin during the period. The list also includes Eritrea, Somalia, Afghanistan, and Iraq – countries that have had high asylum immigration to Sweden for a longer period.

Residence permit to live with someone in Sweden

Of those who came to Sweden to live with someone during this period (i.e., the entire group, not just the six largest countries above), just over 160,000 people have received Swedish citizenship, approximately 36,000 permanent residence permits, and approximately 12,000 have been registered as departed from Sweden.

Chart showing the six largest citizenships who were granted for residence permits to live with someone in Sweden, 2015–2020.

Chart showing the six largest citizenships that have applied for residence permits to live with someone in Sweden, broken down by year.

What is the Swedish Migration Agency doing to combat abuse and crime?

People tend to think of organised crime, welfare abuse and security threats as matters for the police or the Swedish Security Service. But the Swedish Migration Agency also plays an important role in preventing and combating criminality and the abuse of Sweden’s welfare and regulatory systems – as this article will highlight.

Other rules when children become adults

The provisions on family reunification/immigration are based on the idea that families should be kept together – therefore the issue is emotionally charged and raises certain questions when a young adult is to be deported while the rest of the family is allowed to stay in Sweden. How can that happen? In this article, we will answer questions about people who reach adulthood and are no longer subject to the rules on family reunification.

What is the new EU migration and asylum pact about?

The EU has adopted a new regulatory framework reforming the Member States' asylum and migration systems. In this section of the Swedish Migration Agency Answers, you can read about the new rules and how they will affect asylum seekers and migration management in the EU.