The Swedish Migration Agency answers: How is it possible that children who have grown up in Sweden can be expelled?

For obvious reasons, migration cases involving children can spark strong emotions and reactions. It can be difficult to understand and accept that an authority can make a decision to expel a child who has lived in Sweden for a long time – in this article we explain how that works and what the law actually says about children’s rights.

Children are included in all sorts of cases handled by the Swedish Migration Agency. Our cases may involve children with different family constellations or without legal guardians, children who are already in Sweden, or children who are waiting to come here. This article will focus on children living in Sweden who have received a decision that they must leave the country.

How can you be expelled when you have grown up in Sweden?

Being born in Sweden or having lived here for a long time does not automatically mean that you are entitled to a residence permit. Only Swedish citizens have an absolute right to live and work in the country. A Swedish citizen can never be expelled.

A child receives Swedish citizenship at birth if at least one of their parents is a Swedish citizen. There is a common misconception that anyone born here becomes a Swedish citizen, regardless of their parents’ citizenship – but this is not true.

To be granted a residence permit and thus have the right to live here, you must meet certain criteria that are primarily specified in the Aliens Act. If you do not meet the specific criteria, there are no grounds to grant a residence permit, and the Swedish Migration Agency can therefore decide that you must leave Sweden.

There is a section in the Aliens Act that deals with residence permits on the grounds of exceptionally distressing circumstances. This means that the Swedish Migration Agency may grant a permit to a person if, in an overall assessment of the situation, it is determined that exceptionally distressing circumstances exist that mean a person should be permitted to remain in Sweden. In such a case, the Swedish Migration Agency looks at the person’s state of health, adaptation to life in Sweden, and the situation in their country of origin. A child may be granted such a residence permit even if the circumstances that come to light are not as serious and weighty as those required for a permit to be granted to an adult.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child is Swedish law

On 1 January 2020, the Convention on the Rights of the Child became Swedish law, which means that the Convention now has the same status as other Swedish laws – although Swedish authorities, courts and legislators have been obliged to take it into account since 1990, when it entered into force through so-called “ratification”. Among other things, the inclusion of the Convention on the Rights of the Child in Swedish legislation means that an authority that deals with children must consider the best interests of the child, which means that they must always consider what is best for the child.

The best interests of the child do not entail an automatic right to a residence permit

The Swedish Migration Agency must take into account the best interests of the child in all decisions and measures concerning children. There is no clear-cut definition of the best interests of the child; what they are depends on the child’s individual situation. When the Swedish Migration Agency examines whether a child is entitled to a residence permit, the best interests of the child are ascribed a great deal of weight, but this does not mean that a child’s best interests always outweigh other grounds for a decision. The Convention on the Rights of the Child is one of several laws with which the Swedish Migration Agency must comply. It states what rights children should have, but it does not determine who can be granted a residence permit in Sweden. These rules can be found in other laws, primarily the Aliens Act. In cases concerning migration and residence permits, various interests, such as the best interests of the child and Sweden’s maintenance of regulated immigration, need to be weighed against each other. In that balancing act, the best interests of the child weigh heavily but are not decisive.

It can be difficult to understand how a decision that goes against a child’s wishes can still be correct and in accordance with the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The Convention on the Rights of the Child states that authorities must take into account what the child wants and assess what is best for the child, but it does not require that our decisions are always in keeping with what the child wants or what is best for the child. The Swedish Migration Agency may come to the conclusion that it would be in the best interests of the child to be granted a residence permit, but that there is still no scope for this under the Aliens Act. The authority can also make an assessment that says the opposite – that the best thing for the child would be to return to their country of origin.

Click here to read more about the Convention on the Rights of the Child (in Swedish)

Click here for the Aliens Act External link, opens in new window.

External link, opens in new window.

Orderly reception

For a child to be expelled from Sweden without a legal guardian, the Swedish Migration Agency must prove that their orderly reception in their country of origin has been arranged. In an orderly reception, it is primarily the child’s family and relatives, who receive them. In the alternative, they may be received by social services in the child’s country of origin, such as a children’s home or foster home. In some countries, the Swedish Migration Agency cannot ensure orderly reception via the authorities. A common question is how an orphanage can be considered to provide an orderly reception and be better than a home in Sweden – the answer is that the legislation is not designed to make the child’s life in their country of origin better or as good as in Sweden. Rather, it aims to ensure that their reception is sufficiently safe and secure.

A decision can be appealed

If you do not accept the Swedish Migration Agency’s decision, you have the right to appeal to a higher court. The appeal must be submitted to the Swedish Migration Agency, which starts by deciding whether or not the decision should be changed, after which the appeal is submitted to the Migration Court, which takes a position on the matter.

If you are dissatisfied with the ruling of the Migration Court, you can appeal to the third and final instance: The Migration Court of Appeal. However, it is quite unusual for the Migration Court of Appeal to take up a case.

In situations in which a case is granted a review by the Migration Court of Appeal, its judgment will guide the decisions of the Swedish Migration Agency and the Migration Courts in similar cases.

Children’s cases brought before the Migration Court of Appeal

As previously mentioned, a residence permit can be granted on the grounds of exceptionally distressing circumstances. Until 1 December 2023, it was also possible to be granted a residence permit if the circumstances were particularly distressing. Several such cases have been brought before the Migration Court of Appeal and thus serve as guidance for the Swedish Migration Agency.

One example of a case that deals with a child’s adaptation to life in Sweden is MIG 2020:24. In that case, a minor child was granted a residence permit on the grounds of particularly distressing circumstances, and their expulsion was considered to violate the Convention on the Rights of the Child, i.e., it would entail a risk of a so-called breach of Convention. This judgment indicates that factors that may be important for the child’s adaptation to life in Sweden include their age, maturity, schooling, social relationships outside the family, knowledge of the Swedish language, and whether the child has lived in Sweden during their formative years.

Although MIG 2020:24 applies to particularly distressing circumstances, the judgment can provide guidance on the question of what may constitute a breach of Convention within the framework of exceptionally distressing circumstances.

Click here to read MIG 2020:24 External link, opens in new window.

External link, opens in new window.

Is the child’s case affected by their placement in foster care or assignment of a specially appointed legal guardian?

In cases involving children, the Swedish Migration Agency examines the issue of residence permits. The fact that a child lives in a foster home or has been assigned a specially appointed legal guardian in Sweden is not always a basis for a residence permit in itself, but it is taken into account in the assessment of their case.

The Swedish Migration Agency’s cooperation with other actors

The authority that makes a decision concerning a child is responsible for ensuring that the best interests of the child are examined. When the Swedish Migration Agency makes such an assessment in a case, several different sources may provide relevant information, e.g., the child themselves, the Social Welfare Board, or other actors. In other words, the Swedish Migration Agency takes into account the perception of several actors about what is in the best interests of the child – but ultimately makes its own, overall assessment. The Swedish Migration Agency can also help to ensure that another authority makes a correct assessment of the best interests of the child.

Statistics

Zoom image

Zoom imagePress to enlarge.

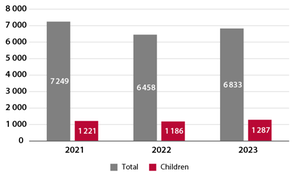

Over the past three years, the number of return cases involving children that concluded with voluntary departure has remained about the same. In 2021, a total of 7,249 return cases ended with voluntary departure, of which 1,221 involved children. In 2022, 6,458 departed voluntarily, and 1,186 of these cases involved children. Last year, 6,833 people left the country voluntarily, including 1,287 children.

“Child” refers to both a child with a family and a child without a legal guardian.